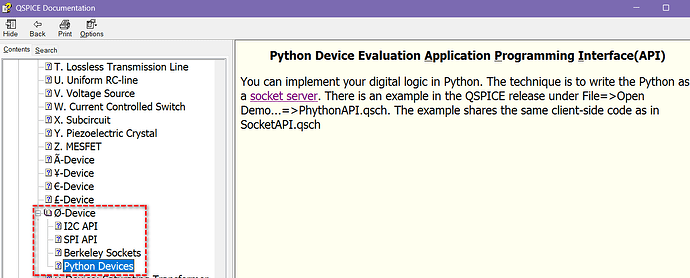

OK, Mike has added template generation and Help documentation. Sweet.

Here’s a bit more information to get folk started.

The DLL Client Stub & Server Template Code

To generate template code, you create the hierarchical DLL block as before. Add/configure ports. Add a string attribute for the server name, port, and program (*.exe or *.py). I think that this must be the second string attribute (after the DLL name) so do this before adding other string attributes. (Note that additional string attributes are not directly supported – see below.) For example:

- For C++ server: “char *server=localhost:1024/SquarerService.exe”

- For Python server: “char *server=localhost:1024/SquareService.py”

If you have multiple schematic instances of the DLL block, you may want to omit the port part (e.g., “:1024”) to let QSpice generate unique ports. Otherwise, I think you must make the port specification unique in each instance.

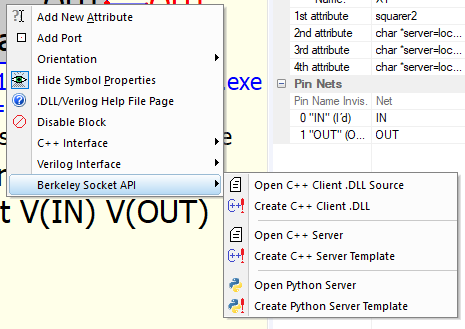

Right-click the block for the expanded template generation menu.

Click “Create C++ Client DLL” to generate the DLL stub code. Likewise, click the “Create … Server Template” to match the server type specified in the second string attribute.

Note: The DLL stub filename is taken from the 1st string attribute. The server code filename is taken from the 2nd string attribute.

DLL Block

You must, of course, compile the DLL stub. It’s C++ code and doesn’t change depending upon the server type. As generated, it passes input port data to the server and sets output port data from the server response message.

Unless you need some custom functionality (e.g., passing non-port data), you should not need to modify this code. (See below.)

If you change the DLL block (add/remove ports, etc.), you should regenerate the DLL stub template code, server template code, reapply changes, and recompile.

Passing Non-Port Data

The generated client stub and server code does not pass anything other than port data. If you want to pass String Attribute data, you’ll need to modify the stub and server code.

The stub code does not include most of the extra “extern ‘C’ __declspec(dllexport)” definitions that are generated but the basic C++ DLL template – stuff like *StepNumber, *NumberSteps, *InstanceName, *ForKeeps, etc. The server code also does not provide this data.

All of the above can be done but that discussion is for another day…

Server Code

The generated server code has comments where you need to add the code for component-specific evaluation, MaxExtStepSize(), and Trunc() functions.

If your component needs per-instance data, simply add global variables in the server code. (QSpice launches a separate instance of the server for each schematic component instance. Global variables aren’t shared between server instances.)

Use-Case Considerations

So, when should you use this fancy new Berkeley Sockets API? The following are my thoughts which (as always) may be irrelevant or incorrect.

- If you want to use Python code for component blocks, this is an easy way to do it.

- You can write a server in another language of your choosing. You could, for example, create a server program in Java.

- If you want to write C++ component code, there might be no advantage. It adds inter-process data communication overhead and you lose direct access to String Attributes and the “extern ‘C’” functions/data. I’m not sure there’s an upside unless there’s a need to run the server on another (faster) machine.

- In all cases, if you want to pass data beyond the input/output port values, you’ll need to write additional code for both the DLL stub and server.

Sorry for the length – just trying to get information out there before I forget. (To be fair, there’s more so it could have been longer.  )

)

If anyone has questions or corrections, please jump in.

–robert

----- Edit -----

The String Attribute that names the server (e.g., char *server=localhost:1024/TestSvc.exe) need not be the second String Attribute. QSpice looks for an attribute with char *server="...". If “server” is not found, it will warn that it cannot create templates. (As stated before, there’s no support for passing other String Attributes to the server without modifying the client and server code.)